Contributed by Darryl Powell, Doc’s Hydraulic-Pneumatic Training LLC

When specifying pneumatic cylinders, you may think that the most important information needed is the bore size and stroke. While these details are certainly important, the application’s requirements are more critical. For example, several questions should be considered: is the cylinder in a wet environment (maybe salt water), is it high cycled, is it a food application with non-lubrication requirement, is it a dirty environment, is there a mechanical disadvantage with high side load, does the load need to stop in mid stroke, and is feedback required on stroke location. I could go on and on for all the unique applications where pneumatic cylinders are used.

First, let’s get the cylinder bore question out of the way. Determine the lowest air pressure that will always be available at the location of the cylinder. This is not the pressure at the compressor which must travel through all the air lines, fittings, and the control valve which requires pressure loss or pressure drop. We will use this information for working pressure (psi) as our starting point and simply divide it into the load (lb) to get the effective area in square inches for the cylinder needed. Quite honestly this information is found in every cylinder manufacture’s catalog. But before you stop here, read the next paragraph to fine tune your selection.

If you want the cylinder to do more than suspend the load, you need to do more calculations. After doing this for some 45 years, my rule of thumb is: take the load and multiply it by 1 ½. So if the load is 1,000 lb, I size the cylinder for a minimum of 1,500 lb load. Very simply it takes a differential pressure for air to move the cylinder. And if the cylinder really needs to move as fast as possible then you want the air to reach what is sometimes referred to as critical velocity or critical backpressure, which is the speed of sound (so maximum speed is achieved when the downstream pressure reaches 53% of the upstream pressure). By oversizing your cylinder bore you can be more confident that your selection will compensate for all the unknown and known variables. The beautiful thing about pneumatics is you simply have to adjust the regulator lower to get the desired results. Now of course, if your application consists of many cylinders, then a prototype would be desirable for testing to verify the most cost-effective choice.

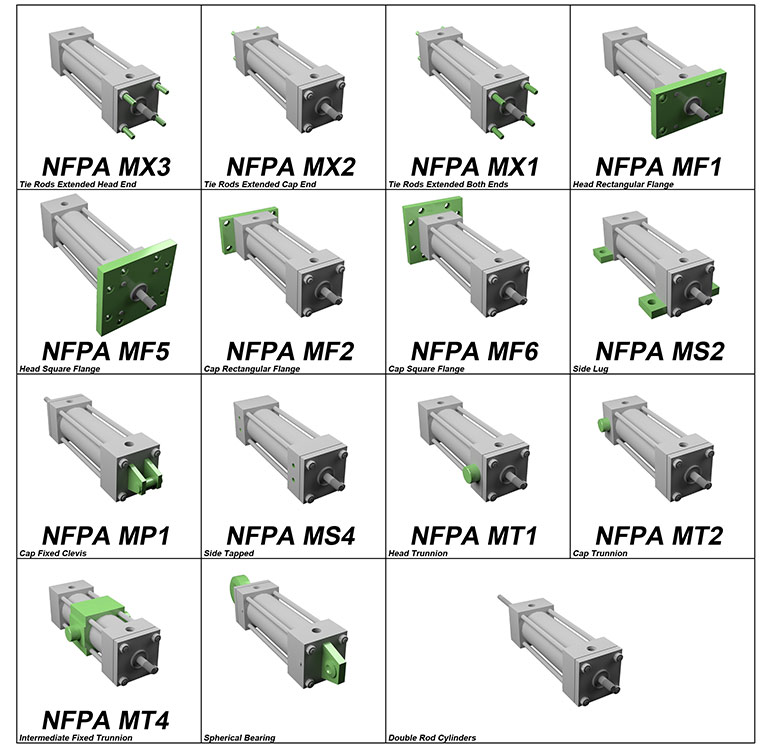

If it is determined that a standard type of cylinder will be used rather than a rodless cylinder or specialty type, then with the bore of the cylinder and stroke known, it is a matter of determining the mounting, size of rod and thread, if cushions are needed (for high speed applications, not to be used to stop massive loads), stop tubing (not as much as a problem as compared to hydraulic cylinders), built in limit switches, etc. Many variables and specials can be accommodated in a cylinder application.

Of course, there are hundreds of types of cylinders, the most common being NFPA tie rod cylinders (heavier duty) with the benefit of interchangeability with other NFPA cylinders. Other popular pneumatic cylinders include non-repairable and round bore type cylinders, typically used for small bore sizes but not always.

Fluid Power Training

fluidpowertraining.net

Filed Under: Cylinders & Actuators, Fluid Power Basics, Pneumatic Tips